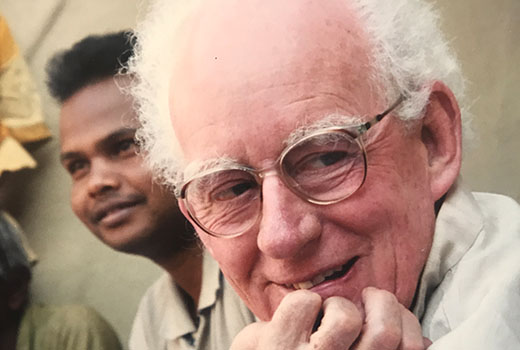

It was the spirit of adventure that led the late Fr Phil Crotty SJ, previous Director of Jesuit Mission and Hazaribag missionary, to India in 1952 and the spirit of devotion that kept him there for 50 years. Written by Catherine Marshall.

When Fr Phil Crotty SJ was a boy growing up in regional Victoria, he couldn’t have known he’d spend his final years praying in a foreign language. It was a lifetime of service, commitment and good old adventure that had brought him to this point – and which had, in the end, carried him full circle. Reflecting on 71 years as a Jesuit, the boy from Ararat, Victoria said he’d joined the Society of Jesus in 1950, at the age of 18, on the assumption he’d be sent off into the world just as soon as the Australian province had found a suitable placement for him.

“At that stage they didn’t have a mission, but the impression I was given was that ‘as soon they get a mission you can be sent on that, otherwise we’ll send you to another province,” he recalled all those decades later.

“So I didn’t know when or where, but it turned out that in 1951 the Australian province was given a mission in India. And that was to become the Hazaribag Mission.”

The enterprise – which ultimately became Hazaribag Province – had arisen from a request by the Belgian Jesuits for assistance at their mission at Ranchi, established in the late 19th century and so successful they now required additional manpower to manage it. The Australian Province, which was scouting around for its own mission, heeded the call, and the first six Australian Jesuits arrived in India in 1951.

When the then-20-year-old Phil followed a year later in December 1952, along with seven other Jesuits, he was embarking on a remarkable journey, one that would deliver the adventure he craved and immerse him in what he would later describe as an “extraordinary revolution”. Until then, the furthest he’d ventured from his home state was Sydney.

I guess it was adventure in those days – not many people went overseas. It wasn’t long after the war, and Australia was pretty conservative about foreign travel and all that sort of thing.”

“We went to, I think it was Myer’s, on Bourke Street in Melbourne, and were given six khaki shirts and six khaki pairs of pants. And that was about the sum total of preparation.”

With the benefit of a lifetime’s worth of retrospection, Fr Phil later ruminated on the courage and commitment required of not only those early Jesuit missionaries – most young scholastics in their twenties – but also their families.

“In those days we went for life. There was no coming back, you know,” he said.

“It was taken for granted that you didn’t see family again, unless they came to India, which they did. But I was probably too young, too excited to really to grasp how painful it was for my mother. And in retrospect, I guess, painful for me. But that sort of feeling comes later, I think.”

Decades later, Fr Phil was able to effortlessly conjure the overwhelming scene that met him when he stepped off the ship in Bombay on Christmas day, 1952. “The crowds, the huge mass of people everywhere, which is, for me, still the most striking difference between India and Australia. Whenever I paid visits to Australia from India, it always seemed to be empty.”

But even if disembodiment and homesickness had struck Phil upon his arrival in India, there would have been little time to wallow in it. The newcomers immersed themselves immediately in the region’s languages and cultures, familiarised themselves with local communities – including tribal people dispossessed of their land – and spent time discerning their own missioned theology. After a few years of collaborative work at Ranchi, the Belgian Jesuits offered their Australian counterparts the northern part of the mission, where they had been least engaged. And so Hazaribag was born – and the Australians in India began to forge their own enduring legacy.

“We had a year of Hindi, and then we were sent out to parishes that were out in the villages.”

“I was sent to a lovely place called Tongo where I spent six months practicing Hindi with the children in the school, teaching some classes and joining the boarders when they went fishing. That was a wonderful time.”

Meanwhile, the young Jesuit’s formation was progressing: he spent time in Pune studying philosophy, taught in schools and at the university college in Ranchi for several years, and completed his theology studies in Kurseong near Darjeeling. He was due to fly from Kurseong to Calcutta in March 1964 to meet his mother, who had travelled to India for his ordination; it would be their first reunion since Fr Phil’s departure from Australia 12 years earlier. But the plane never arrived.

“So to get to the ordination, which was to take place in Hazaribag, I climbed through the window of a train [he had bought a ticket, but it was customary for doors to be locked once the carriage was full] and travelled on the luggage rack all night. And then I got off at a place called Barauni, and travelled all day on a bus, and arrived [in Hazaribag] the evening before the ordination,” he recalled.

“I was covered in dirt from all the roads at this stage, so my plan was to sneak into the house, have a shower, and then go and meet my mother. The first person I met… as I went into the house was my mother, and the first words she said to me were, ‘Typical of you, you’re late!’”

Fr Phil remembered that reunion and the ordination that followed as “wonderful”. But inter-religious tensions were brewing, and during his mother’s visit Belgian Jesuit Herman Rasschaert was stoned to death in Ranchi while trying to protect a group of Muslims from rioting Hindus.

“After my first mass I was actually in Ranchi with my mother, and the news came through that he’d been killed. Immediately there was a lockdown and curfew,” Fr Phil recalled.

“I had to get my mother back to Hazaribag in the middle of this thing. I can remember that was a very nervous journey. I had to get a taxi and the driver said, ‘I’ll take you on condition that we stop nowhere’. She was very cool during the whole thing… but they were forced to cut short their stay in India. My two brothers who were also with her, they decided it would be safer to take her back [home] not long after that.”

The danger of such interreligious mistrust was a familiar concern for the Jesuits. Though they’d been made to feel welcome upon their arrival in 1951, they understood such sentiment hinged on their willingness to develop a deep knowledge and respect for local customs and beliefs.

“If you’re working with tribal people, you must understand their culture, their language, their recent history.”

“People nowadays are so relaxed about other religions, which is a huge change from what it was like when I became a Jesuit – [non-Christians] were people who had to be converted because their religion was wrong, you had to save them, save souls. It’s been an extraordinary revolution, really –it’s like being part of a revolution. It’s made [Jesuits] more human. It’s not me to you, it’s us. It’s not that I’m giving you something, but we’re sharing something together. [But] it takes a long time – you’ve got to learn the language, you’ve got to learn the culture, you’ve got to grow into something.”

With education the cornerstone of the Australian Jesuits’ mission in India – St Xavier’s Hazaribag had been established the year of their arrival, in 1951 – the newly ordained Fr Phil spent time teaching before being appointed a parish priest at Mahuadanr and later Kunda. He was happily fulfilling his parish duties when, without warning and much to his astonishment, he was elected Major Superior (now known as Provincial) of Hazaribag Province. Retelling the story with bemusement decades later, Fr Phil said he’d been en route to Mahuadanr to help elect the new Major Superior when his plans were scuppered.

“We stopped at a parish on the way, and then we moved on and stopped at another parish, and then Fr Bernie Donnelly, who was the superior at the time said, ‘Oh, I’ve left the file at the previous parish’. It was evening at this stage, and we had passed through the jungle, which is locked down at night, they put chains across the road to stop illegal hunting. He said, ‘Can you go back and get the files? So I borrowed a motorcycle from the parish and managed to manoeuvre my way past all the chain gates through the jungle, and arrived about eight or nine o’clock at night back at the previous parish.”

The parish had already dispatched the file with a courier who was now on his way to Daltonganj. Next morning Fr Phil drove to Daltonganj, but the courier had already boarded a bus for Mahuadanr. “So I followed the bus and caught up with it halfway through the jungle, and stopped the bus, got the file and drove on to Mahuadanr myself with the file. And Bernie said to me when I got there, ‘Oh, it doesn’t matter, we’ve already decided, we’re done’. A few weeks later, when the word came through that I was chosen for the job, I was actually having a sleep-in. Bernie came and he said, ‘Look, I’ve come from Ranchi with the message that you’re the Superior’. I said, ‘I can’t be, I was never asked’. He said, ‘We knew you’d say no!’” Click here to read more. Let us join together in the Prayer of Boosting Gratitude, written by Fr Michael Hansen SJ, National Director of the First Spiritual Exercises Program.

First Spiritual Exercises – Boosting Gratitude